They taught us in secret

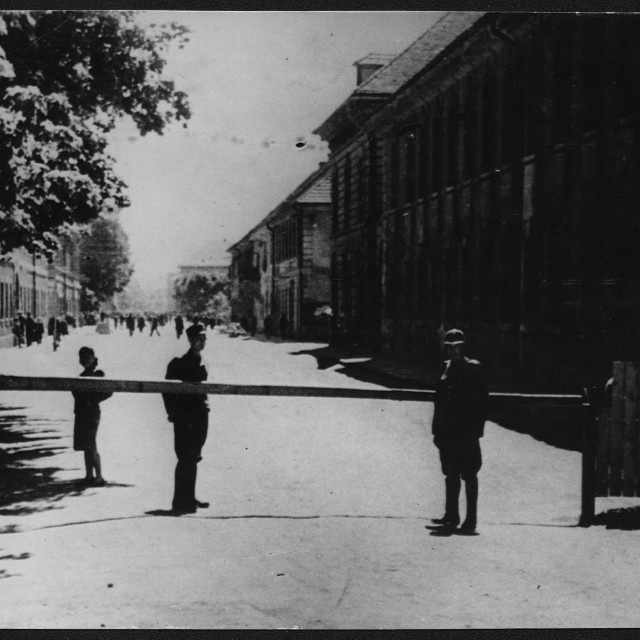

When Mrs. Helga Hošková recollects the time she spent in Terezín as a child during the war, she remarks with gratitude that even though it was strictly forbidden, there were people there who would teach children in secret, in improvised condition: “School teaching was strictly forbidden in Terezín. The children were only allowed to draw and do some handicraft, I think. There were no classes, no boards, no textbooks, no things like notebooks and pencils, but in spite of that we were being taught. All the school subjects. In secret. There were teachers in the ranks of prisoners. But there were also people who were good at something and had knowledge and were simply very fond of children. They would come to us and we would learn.” When the secret lessons were taking place, there was always someone on watch in front of the barrack to warn against unwanted visitors. If someone was approaching the barrack, the person on watch would call out, “a visitor is coming,” which was an innocent remark but the children knew right away that they had to hide pieces of paper and anything that would give away that teaching was in progress. The teachers in Terezín were called “Betreuers,” guardians: “These people had no advantages. If somebody was working in the kitchen or in agriculture, then they would have access to some extra food. But these people had no benefits, nothing. Their services were round the clock. They lived with us in those children’s homes, some of them even slept with some of the children in their room. There were also ill children among us. Somebody had to take care of those too. So, they were guardians, parents, and keepers.”

Hodnocení

Hodnotilo 0 lidí

Routes

Not a part of any route.

Comments

No comments yet.