They taught us in secret

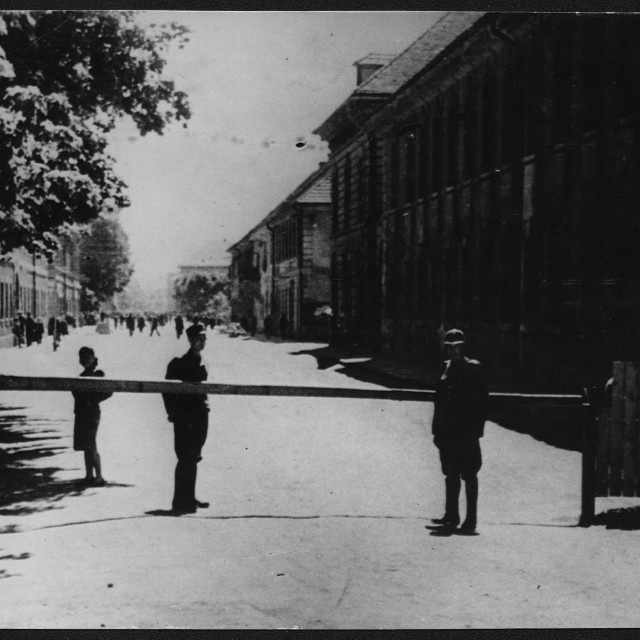

When Mrs. Helga Hošková recollects the time she spent in Terezín as a child during the war, she remarks with gratitude that even though it was strictly forbidden, there were people there who would teach children in secret, in improvised condition: “School teaching was strictly forbidden in Terezín. The children were only allowed to draw and do some handicraft, I think. There were no classes, no boards, no textbooks, no things like notebooks and pencils, but in spite of that we were being taught. All the school subjects. In secret. There were teachers in the ranks of prisoners. But there were also people who were good at something and had knowledge and were simply very fond of children. They would come to us and we would learn.” When the secret lessons were taking place, there was always someone on watch in front of the barrack to warn against unwanted visitors. If someone was approaching the barrack, the person on watch would call out, “a visitor is coming,” which was an innocent remark but the children knew right away that they had to hide pieces of paper and anything that would give away that teaching was in progress. The teachers in Terezín were called “Betreuers,” guardians: “These people had no advantages. If somebody was working in the kitchen or in agriculture, then they would have access to some extra food. But these people had no benefits, nothing. Their services were round the clock. They lived with us in those children’s homes, some of them even slept with some of the children in their room. There were also ill children among us. Somebody had to take care of those too. So, they were guardians, parents, and keepers.”

Hodnocení

Abyste mohli hodnotit musíte se přihlásit!

Strecken

Diese Geschichte ist in keiner Strecke.

Kommentare

Helga Hošková-Weissová

Academic artist Helga Hošková-Weissová, Dr.h.c., was born November 10, 1929 in Prague-Libeň in a Jewish assimilated family. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the family became victim to a number of persecutions by the Nazis, and in December 1941, they were transported to the Terezín ghetto. They spent nearly three years there, and during this time, Helga drew over a hundred of drawings depicting everyday life in Terezín. The picture-cycle, known as Draw What You See, is a precious work and a valuable historical testimony. At the beginning of October 1944, the Weiss family was transported to Auschwitz. While her father died in a gas chamber there, Helga and her mother were later selected to work in an aircraft factory in Freiberg, Germany. In April 1945, they set out on a death march to Mauthausen, where they were liberated on May 5. After the war, Helga simultaneously studied at a secondary graphic arts school and a grammar school. In 1950, she enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, where she studied in the studio of professor Emil Filla. In 1965, she went on a study trip to Israel, which helped her to brighten her palette of colors as well as her outlook on life, and the resulting series of paintings, which she exhibited in spring 1968 in Prague under the title, "Pictures from Wandering Through the Holy Land," became a great success. This opened the door to the world of artists for her; however, shortly after, this door was slammed shut by the invasion of "brotherly armies" the following August. She stopped painting for several years and in the meantime taught at a school for amateur artists. She gradually returned to painting - as well as to the motifs of war, Holocaust, disaster, and catastrophe in general. In her art, she strives to pass the message to the young generation so that they may never commit what had befallen her. In 2009, she was awarded the 1st class State Medal for Merit in the field of culture, art and education, and the Josef Hlávka Medal.